Current Thoughts

(Mostly Hawaii)

When Federal Chaos Reaches the Islands

Driving into the office on Wednesday, January 14, it looked like it would be one of those rare idle days — the kind where you finally clear out the backlog, return a few calls, maybe get ahead of something for once. No fires. No emergencies. No “drop everything” emails waiting in the inbox. Just another quiet workday.

It wasn’t.

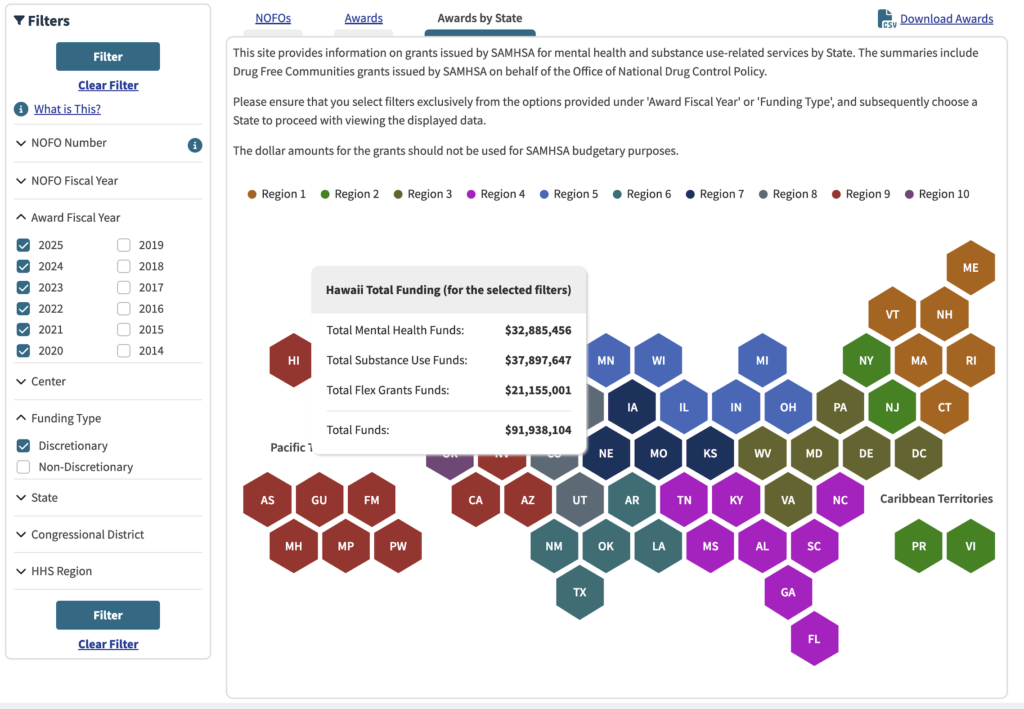

The day started with an email from a program officer at the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Health, informing our campus — Kapiʻolani Community College — that the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), within the federal Department of Health and Human Services, had determined certain awards were “no longer effective to achieve the program goals or agency priorities.”

In plain terms, grants that had already been awarded were suddenly deemed misaligned with current federal priorities — priorities now being reset across agencies by the Trump White House.

PC: PHwSF via the SAMSHA Grants Dashboard found at https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/grants-dashboard

As a result, SAMHSA moved to cancel grants nationwide. According to reporting by NPR, which was tracking the unfolding situation in real time, the scope of the cancellations was sweeping: roughly $2 billion in mental health and substance-use funding, effectively wiped out in one stroke.

For Kapiʻolani, that meant one program was immediately caught in the blast radius: Malama First Responders: Support EMS Personnel Serving Rural Hawaiʻi Through Training, Resources, and Enhancement of Peer-to-Peer Network. The project provides mental health support to Emergency Medical Services personnel — first responders doing demanding, high-stress work in rural communities across the islands.

With the notice in hand and no ability to appeal, the rest of the day became an exercise in damage control: informing department heads, administrators, and partners that a project we had recently extended was, at least for the moment, gone.

Later that day, word came down that folks on the SAMSHA side had not been aware that the termination notices were coming. It reinforced a growing sense that, as with many actions of this federal administration, decisions were made abruptly, with little apparent consideration for how they would be implemented downstream.

Because of its nationwide reach, subsequent reporting by NPR noted that once the termination notices went out, a wide range of vested interests — nonprofits, advocates, and state officials — immediately got on the phone and began pressing members of Congress to intervene.

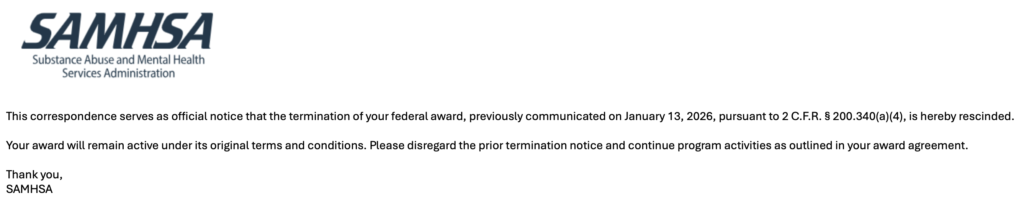

It appeared to have an effect. Within twenty-four hours of issuing the cancellation notices, SAMHSA sent out a follow-up message to grant awardees stating that the terminations were rescinded. In essence: disregard the prior notice and continue operating as you were.

PC: PHwSF

If, as a reader, your reaction to that sequence is something along the lines of “say what?”, you are not alone. As the news spread, the word “whiplash” started circulating, because in the span of a single day, the message shifted from “shut everything down” to “never mind, keep going.”

For those of us who grew up in the 1980s, there was a word for this kind of move: “psyche.” Someone would wind up like they were about to head-butt you, pause just long enough to trigger panic, then brush their hair back and say, “Psyche.”

That, in effect, is what played out here — except this time it wasn’t a schoolyard fake-out. It was federal policy.

So, by the time Friday morning, January 16th. came around, everything had technically returned to where it was just days earlier. Programs funded by SAMHSA were still funded. Award information was restated. The machinery of government clicked back into place. And in the words of Cornelius Fudge, Minister of Magic in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, “so that’s that and no harm done. Pea soup?”

That sentiment only works if you assume the people involved could simply switch off the anxiety, the uncertainty, and the immediate disruption that followed. For everyone else — especially those running programs, managing staff, or serving communities already under strain — the damage wasn’t theoretical. It was real, even if it was brief.

There’s a line often attributed to Lee Kuan Yew, former Prime Minister of Singapore, about governing that feels uncomfortably relevant here: that leadership isn’t a game, and that decisions made at the top carry consequences for real lives below. Systems can’t be knocked down for effect and then declared whole again simply because the order was reversed.

Public health funding, especially in places like Hawaiʻi, doesn’t operate on bravado or impulse. It operates on trust — on the assumption that when the federal government commits, programs can plan, staff, and serve without wondering if the ground will suddenly shift beneath them.

After this episode, that assumption is harder to make, and that may be the most lasting consequence of all.

Goodbyes and hellos: Who explains Hawaiʻi politics now?

PC: “Hawaii State Capitol, Beretania Street, Honolulu, HI – 52221001099” by w_lemay is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Over the past several weeks, a series of articles in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser and Honolulu Civil Beat marked a quiet but consequential shift in who is interpreting Hawaiʻi politics for the public. Two farewells and one arrival point to a change not simply in political voices, but in how the state’s political narrative is being shaped and understood.

The first article that framed this shift was Denby Fawcett’s account of the passing of Tom Coffman, a loss also noted by David Shapiro in the Star-Advertiser on January 4th.

His influence didn’t come from narrating a day-by-day account of politics, but in long-form books that helped readers understand why certain events in Hawaiʻi politics unfolded the way they did. His landmark book “Catch A Wave, A case study of Hawaii’s new politics” told the story of the 1970 Democratic primary for Governor, which was the first election since statehood where the primary for governor became the talk of the town.

PC:US Government Printing Office, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In describing the campaign, the players involved in both (then) Lt. Governor Thomas P. Gill and (then) Governor John Burns’ campaigns, and the angles they took, led Burns to level up, bring in mainland consultants who created a media campaign that is still studied today in Political Science classes.

As a student of Political Science, earning both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree at the University of Hawaiʻi, every course that focused on Hawaiʻi politics either required Catch a Wave or treated it as essential background reading. That status has endured, with the book still widely cited as a foundational text for understanding Hawaiʻi’s modern political history.

That is a legacy that few others reach in the halls of government or society in Hawaiʻi. And this student of Hawaiʻi politics thanks Tom for his contribution to the narrative that still stands on its own to this day.

The second article came out on Sunday, the 4th, when Richard Borreca wrote his last column about the State’s political life in the Star-Advertiser. Every Sunday, before going out for church and other things, this blogger would open up the Star’s website and look for two pieces written almost every week – David Shapiro in the Hawaiʻi section, and Borreca in the editorial pages.

PC: Friends of Ariyoshi/Doi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In fact, Borreca was so influential that when Substack columnist and former reporter Chris Cillizza asked for who the best political reporters in Hawaiʻi were, as he was doing a 50-state stage call of who was the best in each state, this blogger happily listed Mr. Borreca as one of three named, noting that they were the best.

With his retirement, that list now shrinks to two.

In reflecting on Borreca’s contribution to Hawaiʻi’s political narrative, he was a steady demonstration of what institutional memory looks like in practice — drawing on decades of experience at both the State Capitol and Honolulu Hale to remind readers that “what you see now ain’t new… we’ve seen this before.” In his final column, he invoked figures such as former Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi to reinforce that point.

Against those goodbyes comes a very different kind of hello.

Also, on January 4, a Civil Beat piece was issued that spoke about attempts to revive and reframe the Hawaiʻi Republican Party. The article examines issues that have plagued the party for years, if not longer. Further, it examines who the client is that they need to serve, giving a window, potentially, into a new political narrative from a party that has long been marginalized in local politics.

PC: Unknown; dedicated to the Bettman Archive. Likely an organization working with the Senate, e.g. Congressional Quarterly, or the Senate itself., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Outside of Linda Lingle’s two terms as governor, the Hawaiʻi Republican Party has not come close to regaining Washington Place — a reality underscored in 1994, when Frank Fasi’s independent campaign finished ahead of the party in the general election.

Now, one can dismiss this as yet another attempt by the party to move itself from being an afterthought to being a contributor to the political narrative in Hawaiʻi. Whether this new effort will succeed electorally – because the scorecard is tallied by wins and losses – remains an open question. But the fact that a new voice has entered the scene, even if it’s for a blip of time, talking about a subject most have dismissed freshly, potentially could be a new voice that replaces those departing.

The change of voices and their source is not merely stylistic. Hawai’i political punditry has moved from disciplined voices interpreting reality for the public to a faster, more performative space where immediacy is rewarded more than judgment — even though trust is rarely built at speed unless the voice behind it has already earned it.

Coffman and Borreca achieved this through time and interpretive discipline — a standard new voices will have to meet if Hawaiʻi’s political story is to be built on trust rather than noise.

Continuing the work: Politics Hawaii blog 2025 in review

With the end of the year now upon us, Politics Hawaii with Stan Fichtman issues this last article in 2025 with thanks to all of the readers, supporters of the blog, as well as all who have commented on the articles posted this year.

With the way Hawaiʻi, the United States, and world politics evolved in 2025, the blog continued to write on the “World through a Hawaii perspective – the political, social, business zeitgeist – analyzed.”

With the change of administration in Washington DC, the way that administration has rolled out radical changes that affect every state and just about every country in the world, and how that has made analyzing politics even more challenging, this blog continued to just look at the situations, find the story within the story, and tell that story for a deeper, more helpful perspective that was beyond the headlines.

Among other topics, this blog in 2025 wrote about the plan to address homelessness in Honolulu, the reasons why the Trump Administration is now on a colonization drive, the history behind the “airport spur” for the Honolulu rail system that opened up this year, reflections on political icons like Gene Ward, and a new perspective on the assassination of Charlie Kirk.

In all, this blog has written 29 articles this year, about 2 and a half articles a month (between 2 and 3, according to the breakdown). Of course, Hawaiʻi politics (14 articles written) and Hawaiʻi culture (12 written) took up a good chunk of the writing this year.

Other subjects, some new, also came to be part of the blog. We wrote three times about the “Department for Government Efficiency” (DOGE). The president was tagged in 8 posts, and this blog even had 5 opinion pieces, including responding to other bloggers’ posts about subjects like Hawaiian Airlines and about how the state never pays on time.

And throughout the year, up until November, the co-creators of this blog – myself, Stan Fichtman, as the prime writer, and Brandon Dela Cruz, who played a critical role in shaping the product and coming up with ideas to expand the brand – worked hand in hand. Yes, there were times that even co-creators could disagree on the subject of politics – Brandon was a supporter of President Trump and a Republican; I am an independent who never voted for Trump and am a centrist.

But in the end, healthy debate, even if we left subjects as “we agree to disagree,” did help in understanding both sides of an issue, including why people voted for Trump and, in some cases, why they stuck by him when others said he was wrong.

The sharing of ideas on how to expand the blog and the debates about politics and Hawaiʻi society from different standpoints ended on November 10, 2025, with Brandon’s sudden death at the age of 47. There is not a day that goes by that I am not reminded of what he contributed, and how his imprint on so many at his funeral was indelible.

I shall miss my friend and co-creator of this blog dearly.

With the new year upon us, the direction of this blog will remain unchanged. Along with publishing articles that aim to provide a deeper understanding of the political, social, and business stories that affect many, this blog will also continue to apply for the Society of Professional Journalists – Hawaiʻi Chapter awards for 2025. This last year, the blog received a number of awards for its coverage of various subjects.

The longer-term future of this blog will, eventually, need to be addressed. But as Qui-Gon Jinn said to Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, “All right, I’m sure another solution will present itself.”

Until then, may your New Year’s celebrations be bright, and may the return to work after the holidays be less stressful. See you on the other side.

Stan Fichtman – Co-Creator, Publisher and Owner, Politics Hawaii with Stan Fichtman

Co-created with Brandon Dela Cruz (1979–2025), in memoriam

Read past entries of Stan Fichtman and PoliticsHawaii.com!

Other sites that pick up PHwSF

Check out these other news aggregators that pick up Politics Hawaii in their feeds

Hawaii Free Press - Hawaii news aggrigator that is curated by Andrew Walden

All Hawaii News - Another Hawaii-based aggregator from Hilo, HI

Feedspot - Picks up blogs and other publications from all over.

Social Media Feeds

Here is where you can find Politics Hawaii posts on Social Media!

Facebook: Politics Hawaii

Nextdoor: S.J. Fichtman

Instagram (if you want to see nice photos): S.J. Fichtman

Periodically, the blog will also post on Medium, <https://politicshawaii.medium.com/>

Blogroll

Here are some of the other great blogs about Hawaii

Peter Kay's "Living in Hawaii"

Hawaii Free Press - Andrew Walden

Danny DeGraciaʻs Substack (link goes to subscription to read)

What am I listening to?

These are the Podcasters that I am listening to, try them out!

The Lincoln Project (on YouTube)

Chris Cillizza - who makes daily videos on politics (mostly national)

Who am I reading/getting news from

The publisher is choosy as to where the news comes from, here are some dependable sources he refer's to when reading up on topics

Civil Beat (Hawaii on-line newspaper)

Honolulu Star Advertiser (mostly paywalled, but you get free headlines)

The Best of The SuperflyOz Podcast

By Stan Fichtman

The best of my podcasts dating back from Jan. 2018.

Go to The Best of the SuperflyOz Podcast